Here's the best evidence for a TV show boycott I've seen recently. Because, way too often, that medium's producers and writers forget the very real consequences their shows have on the perception of America both abroad and at home. So, in “Whatever It Takes” in the new issue of The New Yorker, journalist Jane Mayer looks at the effect of those prevalent torture scenes in Fox TV's 24 orchestrated by its self-professed "right-wing nut job", co-creator and executive Joel Surnow. I've just read the article, and I gotta say that Surnow comes off as one of Hollywood's biggest assholes. He told Mayer, “We’ve had all of these torture experts come by recently, and they say, ‘You don’t realize how many people are affected by this. Be careful.’ They say torture doesn’t work. But I don’t believe that." But the facts are clear: 24’s regular depiction of torture as an interrogation method has touched off a culture clash between its producers and top military / law-enforcement officials over its effectiveness. Mayer reports: “This past November, U.S. Army Brigadier General Patrick Finnegan, the dean of the United States Military Academy at West Point, flew to Southern California to meet with the creative team behind ’24.” Finnegan…was accompanied by three of the most experienced military and F.B.I. interrogators in the country. [They] had come to voice their concern that the show’s central political premise—that the letter of American law must be sacrificed for the country’s security—was having a toxic effect. In their view, the show promoted unethical and illegal behavior and had adversely affected the training and performance of real American soldiers.” According to Finnegan, misperceptions spread by 24 had made it “increasingly hard to convince some [West Point] cadets that America had to respect the rule of law and human rights, even when terrorists did not.” The experts told 24’s producers that contrary to the impression offered by their show, torture is not just illegal, but also unreliable. Of the show, Joel Surnow says, “Our only politics are that terrorists are bad.” But Mayer points out that “many prominent conservatives speak of 24 as if it were real.” A friend of Surnow’s joked that the conservative writers at 24 have become “like a Hollywood television annex to the White House. It’s like an auxiliary wing.” (Surnow and several others from the show even attended a private luncheon at the White House.) How tragic for TV audiences that, just like that White House crowd, here's another right-winger who won't let the facts get in the way of his ideology. There's only one recourse: stop watching 24.(Okay, her formating sucks... :))

Saturday, February 10, 2007

Yeah, Yeah, We Know TV is Slime But Rightist TV is the Worst

My beloved Nikki:

Thank God George W. Bush is President; Our Leaders Continue to Succeed in Making Us Safer -- Not

They just seem to never get anything right. But this is government, modern rightwing-style: Competence is never desired except in taxcuts and kickbacks. Security is a political platform, not a goal.

From the WSJ:

From the WSJ:

SKY PATROL

U.S. Air Marshal Service

Navigates Turbulent Times

Armed Secret Agents

Have Gripes After 9/11;

Dress Codes Blew Cover

By LAURA MECKLER and SUSAN CAREY

February 9, 2007; Page A1

On Sept. 11, 2001, the Federal Air Marshal Service -- an undercover squad trained to stop or kill hijackers on U.S. carriers -- consisted of just 33 agents scattered on more than 26,000 daily flights around the globe.

None were aboard any of the hijacked planes on 9/11. Six days later, Congress passed legislation calling for a massive expansion of the law-enforcement service as part of the nation's mobilization against terrorism. More than 200,000 people applied to become agents. Soon, thousands of recruits were quietly training in hand-to-hand combat, advanced marksmanship and techniques for discreetly defusing onboard disturbances without ever identifying themselves as marshals.

The service swelled to a current force somewhere between an estimated 2,500 and 4,000. (The exact number of marshals is classified.) Their presence, combined with new provisions allowing U.S. pilots to carry guns in the cockpit, has changed the equation of onboard security. Would-be terrorists now must enter into their calculations a fair chance that a fellow passenger is a well-trained policeman concealing a semiautomatic weapon.

But building and maintaining the force in recent years has been an uneasy ride. Marshals have griped that it's unhealthy flying four or more flights a day and say the job is a monotonous rut that doesn't lead to advancement. Another big complaint: Their cover can be easily blown, particularly when they go through special boarding procedures.

Budget issues led to a hiring freeze, and in some cases resulted in heavier schedules and fewer flights covered. Government oversight bodies, including the House Judiciary Committee and Homeland Security's Inspector General, raised concerns as to whether the marshals were able to do their jobs effectively.

Some marshals say many of their colleagues have quit, although agency officials say defections have been minimal. But Dana Brown, the current director, concedes that the program's $700 million budget wasn't enough to sustain any new hires between July 2002 and fall 2006.

In an interview, Mr. Brown said the agency challenges are largely due to growing pains. "It's the equivalent of having a mom-and-pop or good small business that worked very well and overnight it turned into a large Fortune 500-type corporation with many more issues than it had previously," he said. Mr. Brown is now taking steps to address the marshals' complaints.

The job is a stressful mixture of tedium and high pressure. Marshals have made 59 arrests since 2001 and drawn their weapons only twice -- once shooting a man dead. In the end, none of the incidents were found to be related to terrorism.

Last summer, their secretive operations came into rare public view after Northwest Airlines Flight 42 lifted off from Amsterdam's Schiphol Airport on Aug. 23 for a nearly nine-hour flight to Mumbai, India. Less than two weeks earlier, British authorities had foiled an alleged trans-Atlantic airliner bombing plot, and officials were on high alert.

A group of 11 Indian passengers on Flight 42 attracted the attention of flight attendants and one undercover marshal when they allegedly didn't follow crew member instructions while boarding. Shortly after the DC-10 left the runway, one of the Indian men allegedly handed several cellphones to another, while a third member of the group appeared to be deliberately obstructing the view of what was happening.

Within minutes, as the plane continued to climb, three air marshals on board broke cover and took control of the cabin, moving into the aisles, revealing badges and assuming defensive positions -- according to an internal Federal Air Marshal Service report on the incident and accounts from passengers and crew. A pair of Dutch F-16 fighter jets scrambled to escort the plane back to Amsterdam. Half an hour after takeoff, Flight 42 touched back down, and the Indian men were detained by Netherlands law enforcement.

The incident was a classic demonstration of the marshals' daunting, and often imprecise, task. A potentially dangerous situation was defused with no injuries. But in the end, there had been no security risk at all. The cellphones were just cellphones. All of the suspects were quickly released. Some passengers, particularly Indian nationals, believed the marshals overreacted to plainly innocent conduct.

"We were not passing cellphones," said Shakil Chhotani, a 33-year-old Mumbai exporter of women's garments who was among the arrested men. "Just because one of us was wearing kurta pajamas and four or five of us had a beard, they thought we were terrorists."

Mr. Brown backed up his officers' actions. "I'm comfortable that the federal air marshals did exactly what they thought they should do under the circumstances," he said, noting that the decision was made in consultation with the crew.

President Kennedy launched the air-marshal program in 1961, in response to a wave of hijackings of U.S. flights to Cuba. In the years prior to 9/11, its ranks rose and fell, amid various threat levels and bureaucratic shuffling. Today, after obtaining top-secret security clearance, marshals undergo 15 weeks of preparation for the job, divided between facilities in Artesia, N.M., and Atlantic City, N.J. Each is issued a Sig Sauer sidearm, a small but powerful, Swiss-designed weapon popular in law enforcement.

They are trained to shoot in small areas that replicate airline cabins, practicing with low-powered paint balls. They drill repeatedly through scenarios they might encounter.

The flying force is more than 95% male, and includes recruits from the Secret Service, the Border Patrol, the Bureau of Prisons and the military. The full-time positions pay salaries starting at about $36,000 and average just under $62,000 a year, with a premium for working in certain cities. Marshals travel in teams of at least two, often sitting in first class to be near the cockpit door. Routes considered to be high-risk are given priority.

At the Mission Operations Center outside Washington, stars dot a digital map of the U.S. looming large over the control room, each one representing a plane with a marshal on board. Officials here relay intelligence to marshals in the field and are poised to redeploy marshals if need be.

While marshals train for the most dangerous criminal scenarios, the job is usually uneventful. Many spend their hours in the sky reading. At the same time, they must stay constantly alert.

Marshals say that after flying four or more flights in a single day, they experience fatigue, headaches, and other maladies. Compounding their frustrations, marshals -- mostly in their 20s and 30s -- have little opportunity to advance in or diversify their careers. "Federal air marshals cannot sustain a career in an airborne position, based on such factors as the frequency of flying, their irregular schedules, and the monotony of flying repetitive assignments," the Government Accountability Office concluded in November 2005 report.

Since the post-9/11 expansion, marshals have protested that their anonymity hasn't been adequately protected. Agents are required to check in at airport ticket counters, and in most cases display oversized credentials. Until recently, a jacket-and-tie dress code was mandated on all flights, even those filled with tourists headed for Disney World. They also were instructed to stay in designated hotels, where they had to display their marshal credentials to secure a discounted rate.

To bypass security checkpoints, where notice would obviously be taken of their guns, marshals typically enter concourses through the exit lanes. But they often wait for several minutes while a security guard checks their IDs -- a process that sometimes draws attention from passengers. In some cases, they must enter via alarmed exit doors. "The lights and sirens go off. Everyone turns and looks," one marshal said in an interview.

At the gate, at least one marshal must board the plane 10 or 15 minutes before passengers to check for hidden weapons and meet briefly with the crew. Marshals report being thanked and given the "thumbs up" from passengers who had obviously figured out who they were.

"Without anonymity, an air marshal is reduced to a target that need only be ambushed and eliminated or an obstacle that can be easily avoided," wrote former air marshal William Meares in a letter resigning from the service in 2004. "There is no question that terrorists, using known tactics and methods, can easily determine whether or not a particular flight is covered by air marshals."

Don Strange, the agent formerly in charge of the Atlanta field office, says he repeatedly complained about the stuffy dress code -- internally and to the House Judiciary Committee. "My views were not well received," he said in an interview. Mr. Strange was subsequently dismissed, in October 2005. The Federal Air Marshal Service wouldn't comment on Mr. Strange's termination.

Federal law prohibits marshals from unionizing. But in 2003, mounting discontent prompted them to organize and seek affiliation with the Federal Law Enforcement Officers Association. That gave them a unified voice to deal with management. In October 2003, Frank Terreri, the group's newly elected president, wrote to the agency's then-director, Thomas Quinn, complaining about issues including boarding procedures, dress code, transfer policy and scheduling. In the spring of 2004, the House Judiciary Committee launched its investigation into the service.

Mr. Quinn, a retired Secret Service agent who took over the service a few months after 9/11, told the committee that the problems were exaggerated and that complainers were "disgruntled amateurs" who were bringing the whole organization down.

In February 2006, Mr. Quinn retired from the federal government. Three months later, the Judiciary Committee issued its findings, saying that Mr. Quinn included "factual inaccuracies" in his responses to the committee. The committee also concluded that the check-in and boarding procedures were "unacceptable to ensuring the anonymity of Federal Air Marshals" and criticized the formal dress code and hotel policy.

Now a private security consultant, Mr. Quinn dismissed the report. In an interview, he called those who voiced complaints "insurgents" and "organizational terrorists."

So far, few marshals or security experts believe that the tensions inside the agency have affected the performance of the agents' flights or their judgment in the most critical question they face: when to blow cover and intervene in a situation on board. The decision is more art than science. One air marshal says that officers get drawn into onboard conflicts so often they seem more like in-flight security guards. Says another: "You have to wait until it seems bad before you do anything. You're not a bouncer."

False alarms are sometimes inevitable. Marshals must quickly judge if suspicious behavior is criminal or just odd. They also have to weigh the need to remain undercover as long as possible against the needs of passengers who might be under distress.

"We don't want to ... be drawn out only to find out there was a situation designed specifically for that purpose and now our presence, our positions have been compromised," says Mr. Brown. But even if a situation is not necessarily life-threatening, "We're not going to let anyone get hurt on that aircraft."

In the first of the two incidents when marshals drew their weapons, in August 2002, an agent held the entire coach section of a Delta flight to Philadelphia at gunpoint while his partner restrained an unruly passenger. Once the plane landed, the disruptive passenger and a second flier were detained by authorities but later released and not charged.

The second came in December 2005, when Rigoberto Alpizar, a 44-year-old paint salesman from Maitland, Fla., frantically ran off an American Airlines flight about to leave Miami, with his backpack strapped to his chest. "I'm going to blow up this bomb," he said as he reached into the pack, according to two air marshals who were on board.

When the man, later determined to have been mentally ill, advanced toward the marshals, they shot him nine times, killing him. State prosecutors later concluded that the shooting was legally justified. Calls to Mr. Alpizar's widow, Anne Buechner, weren't returned.

After Flight 42 from Amsterdam, the air marshal service's investigative and training divisions reviewed the incident, according to standard policy, and determined that it had been properly handled, according to a federal official familiar with the process. "It was textbook, that was really the bottom line," the official said.

Mr. Brown, a 25-year veteran of the U.S. Secret Service, took over after Mr. Quinn's retirement. He initially saw the complaints from marshals much as his former boss had. But soon after taking office, he began inviting marshals to small dinners in Washington, and soon came to a different understanding. In July, he sent an email to all air marshals. "Candidly, the morale was much worse than I thought," he wrote.

Mr. Brown has begun taking steps to deal with some of the discord. In August, he loosened the dress code, instructing marshals to "dress at your discretion." A new pilot program allows them to check in for flights at airports using kiosks, rather than ticket counters. The marshals are also free to choose their own hotels. Mr. Brown has set up 29 working groups to address such matters as scheduling and promotions. He's also opened up a dialogue with the officers' association, meeting with its leaders to hear their complaints.

Still, he said he hasn't found a way to change the boarding procedures. In a December memo, he noted that the agency was able to reach its hiring goal for the year, but didn't specify how many new marshals were recruited.

Meanwhile, some marshals who had been highly critical of management "are more optimistic that things are going to get better," says Mr. Terreri.

---- Daniel Michaels and Binny Sabharwal contributed to this article.

Friday, February 09, 2007

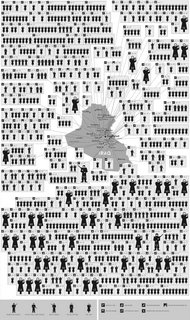

A Comrade With Whom I Agree Regarding Iraq

I'm against leaving; Ted Rall is for it only because he has no faith we -- well, Our Leaders -- can do the right thing and do it properly. He's right about that but still....

First, the good reason to invade Iraq: Penance.The rest is here.

Saddam Hussein was a creation of the United States, armed and financed by the Reagan and Bush 41 Administrations, which used Iraq to wage a devastating proxy war against the new Islamic republic of Iran during the 1980s. Saddam's torture and murder of thousands of Kurds took place under Reagan-Bush's watch.

International reaction to the March 2003 invasion might have been downright favorable if Bush 43 had said something like this: "We Americans have a shameful history of propping up dictators. That policy is no more. Today we go to Baghdad to remove a tyrant we supported, but Saddam is only the beginning of our responsibility to clean up the messes our

CIA has made around the world. After Iraq, our armed forces will remove U.S.-backed autocrats in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Pakistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakh...um, I'll post a list on the White House website."

Second, the good reason to stay in Iraq: Human rights.

If stopping the genocides in Rwanda, the former Yugoslavia and now the Darfur region of Sudan was the right thing to do, why not in Iraq? Soldiers and militia irregulars loyal to the U.S.-installed Maliki regime are carrying out genocidal ethnic cleansing against Iraq's Sunni minority. Tens, if not hundreds of thousands, of Iraqis have been murdered. Millions have been evicted from their homes at gunpoint, forced to flee for the border with nothing but the clothes on their backs. It is our humanitarian obligation to help them, not least because our war started the bloodletting.

Third, the right way to stay in Iraq: Colonialism.

We have 150,000 troops in Iraq. They're stretched so thin that many are now on their third or fourth deployments. There aren't enough of them to control the streets; even the Baghdad airport road is owned by the insurgents. After Bush's "surge," there will be a mere 170,000, still far short of the 400,000 to 500,000 General Eric Shinseki got himself fired as Army Chief of Staff for daring to suggest would be needed to secure occupied Iraq.

Security is the key to everything: economic recovery, political stability, ending sectarian violence. U.S.-enforced martial law and nighttime curfews can keep death squads and insurgents off the streets, creating the conditions that will eventually encourage investment, a free press and the rise of a modern nation-state. But the killers can only be kept at bay if American forces are present on every single street in every town, 24-7. To pull that off in a country the size of Iraq, Shinseki's estimate is, if anything, too conservative.

Of course, this "flood the zone" strategy would ultimately prove fruitless after the eventual American withdrawal. The religious fanatics and other factions who are driving the disintegration of Iraq would merely wait our departure, then fight anew. So there's only one logical conclusion: Don't ever leave.

Forget spreading democracy. If we're serious about dominating the Middle East and access to its oil and gas we have to turn Iraq into a permanent colony like Puerto Rico. As the Brits did in their Indian Raj, America ought to encourage ambitious men and women to seek their fortunes in U.S.-occupied Mesopotamia. They should marry the locals and start families and patrol the streets as part of a new national draft.

What's that, you say? Young Americans don't want to move to Iraq? The United States doesn't have the troops to triple or quadruple our current commitment? Americans don't want to pour trillions of dollars into a hellhole where hundreds of billions have already disappeared?

I've felt exactly the same way--since 2001. Which is why I've been against this endeavor from the beginning. America doesn't have the will, or the budget, to do Iraq right.

Thursday, February 08, 2007

Correction: Maybe Our Leader Actually Leads

Fitzgerald: And had the NIE been declassified at that point?Link.

Libby: It had in the sense that the president had told me to go out and use it with Judith Miller. I don't, I don't know that Mr. Hadley knew that at that point.

Fitzgerald: Okay. And did anyone decide to leak the NIE that week?

Libby: Well, the president had told me to use it and declassified it for me to use with Judith Miller. I don't think Mr. Hadley was told to go out and talk about it. I think Ms. Rice had talked about the NIE in general earlier in the week on television.

Wednesday, February 07, 2007

History Lesson: How Congress Ended One War and Can End Another

We already voted against the Iraq fandango; why can't the Congress we elected?

Jane Smiley (who I worship) thinks victory isn't an option.

I disagree.

Victory is an option. There is no right alternative.

But Our Leaders have no interest in doing what has to be done. What has to be done is against their beliefs. And it's hard work.

As the war in Vietnam progressed, however, and the military situation deteriorated, a few Democrats used the power of congressional investigation to force the administration into a contentious public debate. The most significant proceedings were Fulbright's Foreign Relations Committee hearings in February 1966. Eighteen months after passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, Fulbright decided that he could no longer stand by the president in a war he opposed. He was worried, as were most members of his committee, that the administration's optimistic assessments were wrong and that a huge buildup of troops would be required in the coming years. He also felt personally betrayed by the president, who had promised to act with restraint.More here.

Fred Friendly, who headed CBS News, convinced his superiors to cover some of Fulbright's hearings live and to preempt the normally scheduled shows (such as the popular children's program Captain Kangaroo). In response, the administration scheduled events to distract public attention. The president held a summit with the South Vietnamese leadership in Hawaii the evening before the hearings started. Nonetheless, the Fulbright hearings provided the nation with the first glimpse of such administration officials as Secretary of State Dean Rusk, George Kennan, and former Ambassador to South Vietnam General Maxwell Taylor confronting difficult challenges about the war. When Rusk told the committee that, if the United States did not stand firm militarily, "then the prospect for peace disappears," Fulbright challenged almost all of his assertions. The senator insisted that there was no need to escalate operations in Vietnam because the conflict did not involve the vital interests of America and could easily be a "trigger for world war." The president personally called Stanton to pressure him to take the highly rated hearings off the air. CBS, also concerned about the financial cost of preempting popular shows, obliged.

Johnson came to hate Fulbright, whom he privately mocked as "Senator Halfbright." But the hearings stung the president. Although public opinion remained in favor of the war, Fulbright emerged as a key figure in the growing anti-war forces, though the courtly Southern aristocrat had little if anything in common with the demonstrators increasingly taking to the streets. Indeed, precisely because of his establishment imprimatur, his investigations and statements helped give antiwar protest a certain degree of legitimacy. The hearings also ensured that the mainstream media covered criticism about the war. Fulbright biographer Randall Bennett Woods explained that "the February hearings, in short, opened a psychological door for the great American middle class ... if the administration intended to wage the war in Vietnam from the political center in America, the 1966 hearings were indeed a blow to that effort." Over the next two years, Democrats conducted further hearings, not only on the war but on such related issues as the draft.

Congress also forced the administration to deal with the budgetary consequences of the war. In this case, the pressure came from conservative Democrats. While Johnson believed he could fund both domestic and wartime spending, some members of Congress forced him to make difficult choices. In January 1967, Johnson agreed with his economic advisors to propose a tax surcharge to quell the inflationary pressures caused by the war's overheating of the economy, and to raise enough funds so that he could continue paying for his War on Poverty initiative. But Representative Wilbur Mills, the powerful House Ways and Means Chairman, objected. Mills, a southern fiscal conservative, insisted that if the administration wanted to raise taxes, it would also have to cut domestic spending. Mills feared that the tax reductions of 1962 and 1964 would end in the "Vietnam jungle." According to Mills, Johnson would have to decide between guns and butter.

Because Democrats had lost 47 seats in the House, the conservative coalition had increased its strength, and Mills felt emboldened. While the administration agreed to spending cuts, it did not want to go as far as Mills did. The confrontation escalated in 1968 when an international financial crisis put intense pressure on the United States to reduce its deficit. The Johnson administration finally acquiesced that year and accepted $6 billion in budget cuts in exchange for the tax surcharge. While conservatives were not happy with the tax hike, they were eager to curb the deficit and strike a blow against Johnson's Great Society. At the same time, the tax surcharge "made many doves," as Dean Rusk explained, by making it painfully clear that there were costs to fighting this war. Previously, many liberals had believed that America could support "guns and butter." By 1968, they no longer thought so, and were willing to forego the war to save their ambitious domestic agenda.

* * *

By the time Richard Nixon was elected president in November 1968, the antiwar coalition had expanded in Congress to include such former hawks as Missouri Democratic Senator Stuart Symington and northeastern liberal Republicans like Senator Jacob Javits. Bipartisan alliances were common in this era, since party discipline was weak and the committee system encouraged legislators to work across party lines.

In one respect, the antiwar coalition scored its most important victory when, upon taking office, President Nixon announced his policy of Vietnamization: The United States would gradually withdraw its forces from Vietnam to let the South fight the ground war on its own. Nixon's decision was as political as it was strategic: He had become convinced that he had to end the ground war if he hoped to undermine the liberal media and the Democratic Congress. Nixon's goal was to somehow "break the back of the establishment and Democratic leadership ... [and] then build a strong defense in [our] second term." Initially, his strategy worked. "The president has joined us," Church boasted, "he is now on the same perch with the doves ..."

Notwithstanding this huge policy shift -- and also because it took Nixon four full years to withdraw U.S. ground forces from Vietnam -- Democrats continued to challenge the administration. Nixon's aggressive claims about executive power goaded the opposition. On June 25, 1969, the Senate, by a resounding vote of 70 to 16, passed a "national commitments" resolution that stated that the Senate needed to repair the balance between the branches of government when dealing with foreign policy. That summer, Fulbright demanded that the administration admit there was a secret plan whereby the United States would help fight any insurgency in Thailand. Under pressure, Nixon announced a reduction of the U.S. military presence there. Following a two-week trip to South Asia, Mansfield began to demand that Nixon start reducing the size of U.S. military forces in the region. Some Republicans joined in. New York Representative Charles Goodell proposed a bill that would establish a deadline of December 1970 to pull troops out of Vietnam.

On December 16, 1969, Congress finally used the power of the purse. In a closed floor session, Church and Cooper offered an amendment to a defense spending bill to prevent the further use of money in Laos or Thailand. The amendment received the support of 73 senators. Church called the amendment a "reassertion of congressional prerogatives" on foreign policy. It survived the House-Senate conference committee, and Nixon signed the legislation.

But in the spring of 1970, Church and Cooper became concerned that Nixon was planning to use military force to support General Lon Nol, who had recently taken over Cambodia in a coup. Following Nixon's televised speech on April 30, in which he revealed that he had authorized a bombing attack on Vietnamese forces in Cambodia, Church and Cooper offered a new amendment that extended the 1969 prohibition to include Cambodia.

The administration mounted an intense lobbying effort to keep legislators from supporting the amendment. The American Legion sent letters to senators warning against such action. Historian Robert David Johnson has found that White House Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman authorized what Haldeman in his notes called "inflammatory types [such as Senators Robert Dole and Barry Goldwater] to attack Senate doves -- for knife in back disloyalty -- lack of patriotism." Nixon told his advisors to "hit ‘em in the gut."

Following an intense seven weeks of floor debate over the constitutional balance of power, the Senate voted on June 30, 1970 to pass the Church-Cooper amendment with 58 votes. The amendment stipulated that the administration could not spend funds for soldiers, combat assistance, advisors, or bombing operations in Cambodia. To broaden support for the measure, the sponsors agreed to alter the language so that the amendment aimed to work "in concert" with the administration's policies. They also declared the amendment did not deny any constitutional powers to the president.

Nixon warned that the amendment would "affect the president's exercise of his lawful responsibilities as commander in chief of the armed forces." In contrast to the seven-week debate in the Senate, it took the House less than an hour to table a motion instructing House conferees to agree to the Church-Cooper amendment. In response, Church and Cooper compromised on several key matters, including a provision to limit the amendment to ground troops and not air strikes. They then attached the amendment to a supplemental-aid bill that passed both the House and Senate. While the authors understood that Nixon was already taking troops out of Cambodia, and that the measure would have limited effect, Church still believed the amendment would "draw the purse strings tight against a deepening American involvement in Cambodia." Congress sent the measure to the president in late December. While some antiwar critics preferred the amendment proposed by South Dakota Democrat George McGovern and Oregon Republican Mark Hatfield, which would have required a withdrawal of forces from Vietnam by the end of the next year, the passage of the Church-Cooper amendment marked the first successful use of congressional budgetary authority to limit the war.

The legislative pressure behind the amendment convinced Nixon that he would have to restrict ground operations in Cambodia and elsewhere. State Department official William Bundy recalled that "the Cooper-Church Amendment, and the sentiment it represented, continued to hang over the White House." Nixon National Security Council staffer John Lehman later said that "the impact on executive policies actually ran much deeper. It ... narrowed the parameters of future options to be considered. Everyone was aware that ground had been yielded and public tolerance eroded."

The proposals to restrict funds and force withdrawal produced intense pressure on Nixon to bring an end to the war on his own terms before his legislative opponents gained too much ground. During Nixon's first term, there were 80 roll call votes on the war in Congress; there had only been 14 between 1966 and 1968. In 1971, Mansfield attached an amendment to three pieces of legislation that required withdrawal of U.S. forces nine months after Congress passed the legislation. The White House warned that the president would not abide by this declaration. Congress agreed to pass the amendment but only after deleting the withdrawal date and declaring it to be a sense-of-Congress resolution, rather than a policy declaration, which was stronger. While the Senate had watered down the amendment, the expanding number of votes in support of it made the administration well aware of an increasingly active and oppositional Congress.

In 1972, Church and Senator Clifford Case of New Jersey were able to push through the Senate an amendment to foreign-aid legislation that would end funding for all U.S. military operations in Southeast Asia except for withdrawal (subject to the release of all prisoners of war). Senate passage of the legislation, with the amendment, marked the first time that either chamber had passed a provision establishing a cutoff of funds for continuing the war. Though House and Senate conferees failed to reach an agreement on the measure, the support for the amendment was seen by the administration as another sign that antiwar forces were gaining strength. The McGovern-Hatfield amendment was enormously popular with the public. A January 1971 Gallup poll showed that public support for the amendment stood at 73 percent.

During the final negotiations with the Vietnamese over ending the war, culminating with the 1972 Christmas Bombings and the Paris Peace Accords in January 1973, the president knew that he only had a limited amount of time before Congress finally used the power of the purse to bring the war to an end -- regardless of what the administration wanted. Indeed, to make certain that the president could not reverse course, in June 1973 Congress passed legislation that included an amendment sponsored by Church and Case to prohibit the use of more funds in Southeast Asia after August 15. Sixty-four senators voted in favor. When the House assented, its vote marked the first time that chamber had agreed to cut off funds, too.

Most importantly, Congress passed the War Powers Act in 1973 over Nixon's veto. The legislation imposed a series of restrictions on the executive branch to ensure that the president would have to consult with the House and Senate before authorizing the troops for long periods of time.

* * *

For the remainder of the decade, congress continued to legislate its ideas about U.S. conduct in the Cold War and to restrict the authority of the executive branch. In 1975, Congress refused President Gerald Ford's last-minute request to increase aid to South Vietnam by $300 million, just weeks before it fell to communist control. Few legislators had taken the request seriously; many conservative Republicans and hawkish Democrats agreed by then that Vietnam was lost and that the expenditure would have been a waste.

Nor did Congress restrict its actions to Southeast Asia. Congress passed an amendment in 1976 that banned the use of funds to fight communist forces in Angola. Frustrated with these decisions, Henry Kissinger complained that "we are living in a nihilistic nightmare. It proves that Vietnam is not an aberration but our normal attitude." Angola fell to communists. Although Democrats were not happy with the outcome, most remained convinced that Americans did not want to enter another protracted conflict. One cartoonist at the time quipped: "If you liked Vietnam, you'll love ... Angola."

Congress also tackled the important national security issues of covert operations and intelligence. Hearings by Church pressured Ford into issuing an executive order that imposed restrictions on the CIA, including a ban on assassinations. Ford agreed to issue the order, rather than waiting for inevitable congressional reforms, after then–Chief of Staff Dick Cheney told him such action would protect the CIA from "irresponsible attack" and protect presidential authority. In 1978, Congress passed the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which required court-supervised monitoring of domestic surveillance operations by the federal government. The reforms were a response to revelations that the government had rampantly abused its power throughout the Cold War.

In sum, Congress played a very important role in building opposition to an unpopular and failed Cold War intervention. Legislators emerged as major voices of skepticism, criticism, and outright opposition to Vietnam. They checked the hawks in the administration who refused to believe the facts on the ground. Congress was ultimately pivotal to placing pressure on the Nixon administration to end a conflict that cost approximately 58,000 American lives.

Today, members from both parties would benefit by looking back at the history of Congress in the Vietnam era. As Congress struggles over how to correct a failed military policy and how to deal with an administration that is refusing to change course, legislators need to draw on their resources -- in the tradition of Fulbright, Church, McGovern, Cooper, Hatfield, and others -- despite the political risks. The real risk would be for Congress to capitulate and fail to act on its disagreement with the administration. The costs of the war in Iraq have been enormous, as financial and military resources, and human lives, are drained away. If voters go the polls in 2008 with the same fire in their bellies they had in 2006, the electoral costs will also be high for incumbents who failed to act on their beliefs.

Jane Smiley (who I worship) thinks victory isn't an option.

I disagree.

Victory is an option. There is no right alternative.

But Our Leaders have no interest in doing what has to be done. What has to be done is against their beliefs. And it's hard work.

Tuesday, February 06, 2007

Monday, February 05, 2007

The Gulf of Tonkin 2: Najaf 2007

(Wiki or Google "Gulf of Tonkin".)

It couldn't of happened at a more convenient time for Our Leaders and their surge.

It couldn't of happened at a more convenient time for Our Leaders and their surge.

So far, there are 2 things that we can say with certainty about the massacre of 250 Iraqis outside Najaf on Monday. First, we know that there is no solid evidence to support the official version of events. And, second, we know that every media outlet in the United States slavishly provided the government’s version to their readers without fact-checking or providing eyewitness testimony.More here.

This proves that those who argue that mainstream news is “filtered” are sadly mistaken. There is no filter between the military and media; it’s a direct channel. In fact, all of the traditional obstacles have been swept away so the fairy tales which originate at the Pentagon end up on America’s front pages with as little interference as possible.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)